Introduction

Today is Father’s Day. It’s appropriate that we discuss the Bible on Father’s day. Dad’s Words have power. They can build up or tear down. They can carry tremendous weight. We should use them well, and in doing so, we reflect our heavenly Father.

Throughout this series, I have encountered more questions about Bible translations than about any other topic. Maybe you have faced similar questions. How do you know your translation is best. Or maybe asking about how we can trust the words in our English Bibles, not because of Bible translation but because of discussions about the various manuscripts.

The Right Words Matter

I’d like to revisit a few passages that we have already examined throughout the series. The first is one that has been a theme passage during the series, 2 Timothy 3:16-17

16 All Scripture is breathed out by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, 17 that the man of God may be complete, equipped for every good work.[1]

Next is 2 Peter 1:21

21 For no prophecy was ever produced by the will of man, but men spoke from God as they were carried along by the Holy Spirit.[2]

Both of these passages emphasis the importance of Scripture and that it is given by God. This was the focus of our very first week of the series, the inspiration of Scripture. The doctrine of the inspiration of Scripture influences all the other attributes we discussed. It’s also important for our topic this morning. If the Bible is not only human words, but also divine words, then having the right words matter. Remember another passage that we looked at, when we discussed inerrancy, it was John 10:35

35 If he called them gods to whom the word of God came—and Scripture cannot be broken—[3]

If you remember, what is significant in this verse and how it relates to this doctrine, is that Jesus responds to a charge against him by making a Biblical argument. But within that argument he drops this beautiful truth, Scripture cannot be broken. He states his Biblical argument then gives the warrant for his argument – that Scripture cannot be broken – which leads to his conclusion. What is remarkable is that this proof or warrant is merely asserted. In other words, this is something that all parties agreed upon. It means that every aspect of Scripture is important and worth our attention. The words matter.

But, of course, this raises the question: Do We have the right words? Can we trust the words in our Bibles?

We Can Trust the Words in Our Bibles

We don’t have the original manuscripts, and that’s ok.

Not only do we have the right books, but those right books have the right words. Sometimes you may hear the accusation “our Bibles are just copies of copies of copies of copies. We can’t really trust them.” If it’s important that we have the right books, it’s also important that the books contain the right words for us. As we mentioned when we discussed inspiration, it relates to the original manuscripts. But the problem, of course, is that we don’t have the original manuscripts. But is this really a problem? Was God’s intention ever for us to have the original manuscripts?

There are three different things that God could have done.

Option 1. He could have made it so copy errors never happen. He supernaturally prevents people from making errors why copying Scripture.

Option 2. He could have preserved the originals. But we might think, how would the document last that long? Also, it would give some person or some group exclusive control over the Scripture. It would be centralized and subject to alterations, or kept from the public.

Option 3: Preserve the original words through many copies.

Variants (differences) are noticed and don’t change the message

Don’t get swayed by the rhetoric

People say that “there are more typos than there are words of Scripture.” But that expression says more about the number of manuscripts that were being produced than the number of errors. The reason there are so many variants is that the Bible was being disseminated like no other book before or since. We should also recognize how this number is achieved. Scholar Bart Ehrman is known for his criticisms of the Bible and often throws out flippant numbers like “200,000…no, 300,000… even 400,000.” The tactic is meant to stun and confuse, but we need to recognize what he’s doing. First, no one knows the exact number because they are not counting it. Second, he often includes translations of manuscripts and sermons and quotes in church history as a part of it. Third, we need to recognize how it’s counted. If there is a manuscript that say “Jesus walked to the water.” And 50 that said “Jesus walked down to the water.” We might think that means there was one variant. No, it would be counted as 51 differences. Finally, it’s not as if the differences happen everywhere all the time, they cluster around certain passages and are easily recognizable.[4]

Differences noticed in text trees

It’s not like the telephone game where there is one line of communication from one person to the next, all the way down the line. Instead there are multiple lines. Or what scholars call manuscript trees. Where we can see how one manuscript influenced the next. We also have more than only the manuscripts since we have sermons and quotes from the early church. Skeptics love to add these in to accumulate differences, but we can see the enormous benefit of having works from various times quoting Scripture. We can compare what they said and when they said it to the manuscripts of that time period.

Go here for a helpful illustration of this idea.

They don’t take away from the message

It’s not as if we are missing part of Scripture, some have said it’s like having a 1,000 piece jigsaw puzzle with a 1,005 pieces.[5] Somehow, few extra pieces got mixed in there. It doesn’t change the big picture, we have all that we need, but there are a few bits that need to be sorted through.

Greg Gilbert gives a helpful example of how this takes place,

Now we are engaged in a great civil war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives so that the nation of which we speak might live.

He explains that we can notice how a Scribe can miss a section because of the repeated use of “war.” The other difference is “that that” and “that the.” Typically Scribes would smooth out the reading, so the original is typically the clunkier reading.

We also need to recognize that the variants are not found all over the place, but are typically in clusters or similar passages. The most significant variants are the account of the woman caught in adultery in John 8, the ending of the Gospel of Mark, and the Johannine Comma in 1 John 5:7-8.

Text Traditions can influence Translations

While we can trust this work, we should recognize that people come at the text traditions differently. There are main streams of texts, and many scholars search out the oldest texts and seek to compare and contrast. Others take the majority text of a particular passage – meaning the readings that have the most manuscripts and hold to that reading. Some of the issues with this is that the Byzantine texts, because it was being copied in areas where people spoke Greek, tend to have more evidence. In other areas that relied on the Latin translation, we don’t have as many manuscripts. More isn’t necessarily better.

The Byzantine texts seemed to have a fuller reading. So you might have in these texts something like “The Lord Jesus Christ.” And you may have in the Alexandrian texts “The Lord Jesus.” The question might be, is one adding or is one taking away? Is one trying to take away from the title, or Jesus, was another adding to it? There was what is called the expansion of Piety. We tend to do this ourselves. We have a healthy respect for Jesus, and it seems better to refer to him by name if possible, or with reference to Lord or Christ. This is likely what happened with Scribes as well. We might think what is more likely, that someone intentionally tried to limit the title of Jesus, or that a devout Scribe unintentionally added. This is important because the Byzantine text is the basis for the King James Version, and many modern translations pull from a variety of texts. Sometimes you will hear that modern translations are trying to devalue Jesus. But it can be helpful to see why the translations are doing what they are doing. If there is a conspiracy to limit Jesus’ title, it doesn’t seem to be working well when the KJV uses the full title 86 times, the NASB uses it 64 times, and the ESV uses it 63 times. It’s not as if it disappears from usage or is a mere mention. It’s still found throughout the New Testament.

We Can Trust the Translations of our Bibles

Can we really take a language that looks like this,

Μὴ θησαυρίζετε ὑμῖν θησαυροῦς ἐπὶ τῆς γῆς, ὅπου σὴς καὶ βρῶσις ἀφανίζει, καὶ ὅπου κλέπται διορύσσουσιν καὶ κλέπτουσιν· θησαυρίζετε δὲ ὑμιν θησαυροὺς ἐν οὐρανῷ, ὅπου οὔτε σὴς οὔτε βρῶσις ἀφανίζει, καὶ ὅπου κλέπται οὐ διορύσσουσιν οὐδὲ κλέπτουσιν· ὅπου γάρ ἐστιν ὁ θησαυρός σου, ἐκεῖ ἔσται καὶ ἡ καρδία σου,

and have any confidence that this,

Do not lay up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and rust destroy and where thieves break in and steal, but lay up for yourselves treasures in heaven, where neither moth nor rust destroys and where thieves do not break in and steal. For where your treasure is, there your heart will be also (Matt. 6:19–21),

means the same thing?

Well, the answer is, “Yes, but not without a lot of work.” Any translation project requires years of effort first in understanding the meaning and structure of both languages and then in finding words and structures in the target language that accurately capture the meaning of the original. To put it less technically, translation is a matter of understanding the meaning of a word or sentence and then laboring to say the same thing in different words that will be understandable to a different person.[6]

My goal in discussing translations is to inform about the various methods, but my hope is that in doing so, it helps us understand them better while also giving us confidence in our English Bibles. There is a danger or temptation that some have of trying to cause doubt in our translations in order to market oneself as the expert. Often, pastors and scholars can come across like, “All translations are just translations, if you want to know the real meaning – come to me, the expert, and I will tell you all you need to know!” This kind of hubris should be rejected.

As we have seen, people were instructed to teach their kids the Scriptures, and the Bible was written in ordinary language. Not only that, in Jesus’ day, it was common for people to read and quote the Greek translation of the Old Testament. This is important for us to understand when we think about whether translation is even possible. If it’s to be avoided, it is curious that we have the New Testament quoting Old Testament passages in the Greek translation. As the Lexham Bible Dictionary says, “It was the Bible of the apostolic church—the writers of the New Testament quote from it extensively.[7]”

We see Jesus quoting Psalm 22, not in Hebrew but in Aramaic, while on the Cross.

And early in the history of the church, we see the Bible translated into Latin. Throughout church history, people have made God’s Word accessible. However, there was a period when the laity did not have the same level of access, and the Reformation sought to correct this by translating the Bible into common languages. Teachers and scholars certainly benefit the church, but we can have confidence in our Bibles.

Use multiple translations to aid in Bible study

Mark Ward gives an example of Psalm 16 for how Bible Translations can be mutually beneficial,

Let me give just one example; I could give thousands if my memory were a little better, because I’ve been ferreting out these insights for years as part of my regular Bible study.

Psalm 16:6 in the KJV reads:

The lines are fallen unto me in pleasant places; yea, I have a goodly heritage.

In the NASB we get something not much different:

The lines have fallen to me in pleasant places; Indeed, my heritage is beautiful to me.

The ESV is also similar:

The lines have fallen for me in pleasant places; indeed, I have a beautiful inheritance.

I can read Hebrew, and I can tell you that none of these translations is “wrong” in any way I can figure. But I read this poetic statement many, many times and never understood it. What are the “lines”? I asked another long-time reader of the KJV, and he guessed that David is talking about lines of genealogy. He was a step ahead of me because at least he had a guess. To my shame, I can’t say I ever even stopped to ask, or noticed that I wasn’t getting it. I think I always assumed that it was just a very obscure way of saying that things were going well for David. (Don’t we all like it when lines are, um, falling just right?)

But one morning while on a business trip in West Virginia, I was reading my Bible on my laptop because I had forgotten my paper Bible. I was reading through Psalm 16, and when I arrived at Psalm 16:6 I could easily see two other translations that instantly solved the puzzle I didn’t know was there:

The NIV read:

The boundary lines have fallen for me in pleasant places; surely I have a delightful inheritance.

The HCSB was similar:

The boundary lines have fallen for me in pleasant places; indeed, I have a beautiful inheritance.

Boundary lines! Now that makes sense. Why didn’t I think of that before? Largely, I think, because of the KJV word “heritage” at the end of the verse. It’s a fine word, but my sense is that today we rarely use it to mean the inheritance of physical property. Instead we speak of the “heritage” of shared values or traditions in a given culture or family. A heritage is an intangible inheritance, but David was talking about a physical one.[8]

The idea, though, is to understand the difference between the translation and the text. In other words, it does more harm than good to pitch one translation against another. Instead, they both can serve the goal of understanding the inspired text. The NIV can help with the obscurities of the ESV or NASB, but when we recognize what it’s seeking to do, we can see how it complements other translations. We could take the NIV to be a definitive reading or we could see it as maybe making an interpretive move because of the style of translation.

Recognize translations have their strengths and weaknesses

Here’s the truth: if we are going to sit out and read the Bible in the morning, we don’t really want to wade through “Jesus to the water, he walked.” Or “Walking, they, to him, talked.” Jesus walked to the water, or they talked to him as they walked, are readable and won’t drive us crazy as we relax and seek to read a portion of Scripture. However, the more in-depth we become, the more helpful it can be to have more formal translations. We typically preach from the ESV on Sunday mornings, but that doesn’t mean that’s the only helpful translation or even the best translation for you as you read it during the week or teach it to your kids. We have Bibles in the chairs that are both ESV and NIV. Both are solid translations. The Christian Standard Bible or the New Living Translation can also be helpful. I will admit, I was not a fan of the New Living Translation early on, particularly its use of John 3:16, but it has had several revisions and is solid thought-for-thought, though it does lean more that way than the NIV or others.

There can be times when it’s very obvious. We might say the car of my sister. This can be translated as “My sister’s car.” There are times when ‘of’ can describe the type of car instead of the possessor of the car, like the car of carbon fiber. This describes the material of the car. Technically, the phrase the car of my sister could be a car composed of a person’s sister. But that’s obviously not what it means. There are other ways that this can be used as well. Most of the time, these things are clear. But when it comes to abstract concepts in Scripture, sometimes it can be a challenge. Some translations seek to clarify these issues for us but in doing so can narrow the interpretation. Let me give you one example I came across this week.[9]

James 2:12 [ESV] “So speak and so act as those who are to be judged under the law of liberty [nomou eleutherias].” [NIV] “Speak and act as those who are going to be judged by the law that gives freedom.”

Kevin DeYoung comments on this,

The NIV interprets the law of liberty to mean the law that gives freedom, but the Greek is ambiguous. The phrase nomou eleutherias may mean that liberty is the law under which we are to be judged, or that liberty is characteristic of the law, or that the law imparts liberty, or some combination of all of the above. The ESV allows for all these possibilities; the NIV does not.[10]

It certainly could be correct here, and it simplifies the text, but it might remove ambiguity that causes us to ask interpretive questions and get to the meaning. DeYoung is making this point because he is advocating switching his church from the NIV to ESV for preaching. His concern is that the more formal text allows the ability to explore the options.

Another example of smoothing things out but narrowing meaning is found in Acts 19:11

The ESV says

[ESV] “And God was doing extraordinary miracles by the hands [tōn cheirōn] of Paul . . . ”

[NIV] “God did extraordinary miracles through Paul . . . ”

Here we see both translations have God as active working through Paul, but one interprets the expression hands of Paul as a figure of speech to refer to Paul’s agency. The other retains the word hands, this leaves open the possibility that the text purposefully includes hands. This may be because Paul was doing miracles, such as healing, by laying his hands on others. The NIV can limit this interpretation. I have a chart of various translations for this verse that can be helpful. You see that the NLT makes another interpretive move, which seems to push the main agent from God to Paul and adds the word power. Will these differences prevent us from living a faithful life to the Lord? Absolutely not. In fact, they are minor differences that exist because the translations are trying to do different things. This shouldn’t cause us to lose confidence but to recognize the strengths and weaknesses of each approach.

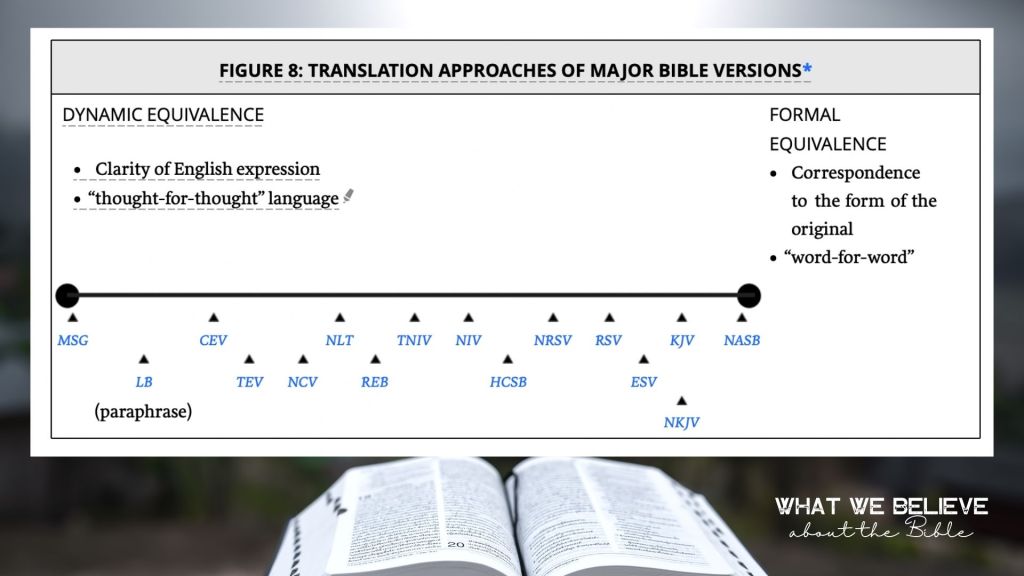

This image can show the differences. Note: the percentage is how much the differ from the ESV.

C.S. Lewis wrote,

“As for translations, even if one doesn’t know Greek (and I know no Hebrew myself) we have now so many different translations that by using & comparing them all one can usually see what is happening.”[11]

Know the difference between translation and paraphrase

I will say that we need to be careful of having a translation that is by one person instead of a committee. It can be easy to include interpretations in the translation, and a committee can circumvent that. Also, as gifted as one individual may be, we need others and their expertise. Also, paraphrases should not be treated as translations. They can be helpful to understand hard parts of the Bible and can be a guide alongside a translation, but they are not translations themselves. Think of them like a commentary or devotional rephrasing of a Bible passage. An example would be the Message.

Here is an image that shows the spectrum of translations. This is from Robert Plummer’s book 40 Questions About Interpreting the Bible.

Conclusion

Which is the best? Again, this question could very well be answered “it depends.” While I mentioned how the NIV can limit some interpretive possibilities, it also brings much clarity to otherwise obscure passages. There are trade-offs. If you struggle with the clunkiness of something like the ESV, maybe the flow of the NLT, CSB, or NIV is better for you and will keep you engaged. Most interpretive moves are backed up by other passages in Scripture, you are not being led astray, and it can help you stay engaged. If you read two chapters a day using the NLT and can only make it through one paragraph a week with ESV, then stick with the NLT.

There are benefits of having one go-to translation and a mix of other translations. Having one can help you memorize Scripture as you see it over and over with the same words. Even having a go-to Bible can be helpful because you might remember that something was in the book of Matthew on the top-right page. But having other translations that you visit, read at length, and consult can be important as well. We don’t need to be glued to one translation. It’s funny when people pit one against the other; we are so prone to divide into factions. We see this in the early church – I’m of Paul, I’m of Apollos. We can be team NIV, team ESV, but as Paul said “what are we, we are all of Christ.” It is God who works through His Word. We can benefit from the gifts of all who work on manuscripts, translations and the like. Faith comes by hearing and hearing the word of Christ, and praise God that he has made His word available to us through so many means.

There is some benefit to wrestling through the pros and cons of various translations, and there are settings where that’s appropriate, but don’t be the person looking at all the various meals that he has available and debating their nutritional value while starving to death. Take up and eat.

We have a trustworthy witness in our English Bibles, and we can use it to learn, grow, and pursue the Lord. But God has also given us an image. Something that churches in every language can participate in. And that’s the Lord’s Supper. Here we get a picture of the gospel message and what Jesus came to do for us. This is what we celebrate this morning.

[1] The Holy Bible: English Standard Version (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles, 2016), 2 Ti 3:16–17.

[2] The Holy Bible: English Standard Version (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles, 2016), 2 Pe 1:21.

[3] The Holy Bible: English Standard Version (Wheaton, IL: Crossway Bibles, 2016), Jn 10:35.

[4] For more see, Greg Gilbert, Why Trust the Bible?, 9Marks Ser (Wheaton: Crossway, 2015), 50-51.

[5] I first heard this analogy through Do Non-KJV Bibles Delete Inspired Words?, 2022, https://vimeo.com/742847080.

[6] Greg Gilbert, Why Trust the Bible?, 9Marks (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2015), 30–31.

[7] J. William Johnston, “Septuagint,” in The Lexham Bible Dictionary, ed. John D. Barry et al. (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2016).

[8] Mark Ward, Authorized: The Use & Misuse of the King James Bible, ed. Elliot Ritzema, Lynnea Fraser, and Danielle Thevenaz (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2018), 128–130.

[9] I found this example in DeYoung, Kevin. Why Our Church Switched to the ESV (Function). Kindle Edition.

[10] DeYoung, Kevin. Why Our Church Switched to the ESV (Function). Kindle Edition.

[11] As quote by Mark Ward, Authorized: The Use & Misuse of the King James Bible, ed. Elliot Ritzema, Lynnea Fraser, and Danielle Thevenaz (Bellingham, WA: Lexham Press, 2018), 130.